By Dr. Kenneth L. Scott Jr., DO, CMD

Elaine (not her real name) was 57 years old when she arrived at our facility for rehab following a fall at home that left her with a fractured tibia, requiring surgery at the local hospital.

Elaine seemed quite stable upon arrival, but as I continued her initial interview and physical exam, it became clear that although physically doing well, she exhibited unexplained confusion. As the conversation progressed, I became alarmed that a 57-year-old woman—who was recently living alone, working, and multitasking—could have such a significantly altered mental status.

The hospitalist at the acute care facility had mentioned her confusion and was concerned enough to have a neurologist consult. It was felt that this could be some post-anesthesia confusion but that she was stable enough to come to our facility to start her rehab.

At this point in the process, many nursing home personnel would have followed the lead of the hospital’s discharge diagnosis. But let’s see why doing so could have led to a drastically different result for Elaine in the short and long term.

Source of Confusion

Following her surgery, Elaine’s initial orders were for partial weight-bearing on her left leg. I immediately saw that her ability to follow commands—to protect her left leg and partially bear weight on it—was going to be difficult for her based on the level of her confusion.

On the day of her admission, I initiated a full metabolic workup looking for any source of her confusion. In my immediate opinion, her confusion was too severe to be related to anesthesia and too sudden in onset to be readily ascribed to early-onset dementia. Furthermore, I was concerned about why someone as active as her would have fallen at home in the first place.

Looking back at old records, I could see that she had been diagnosed in the past with neurosarcoidosis. Upon her arrival at our local hospital, however, she was on no medication for this condition. Lab work did not reveal a cause for her confusion. Thus, although her vitals were stable, I ordered a spinal tap.

Over the next 48 hours, the results of her lumbar puncture returned, consistent with a flare of her neurosarcoidosis. Multiple conversations were had between her neurologist and her rheumatologist, and she began therapy with high-dose steroids.

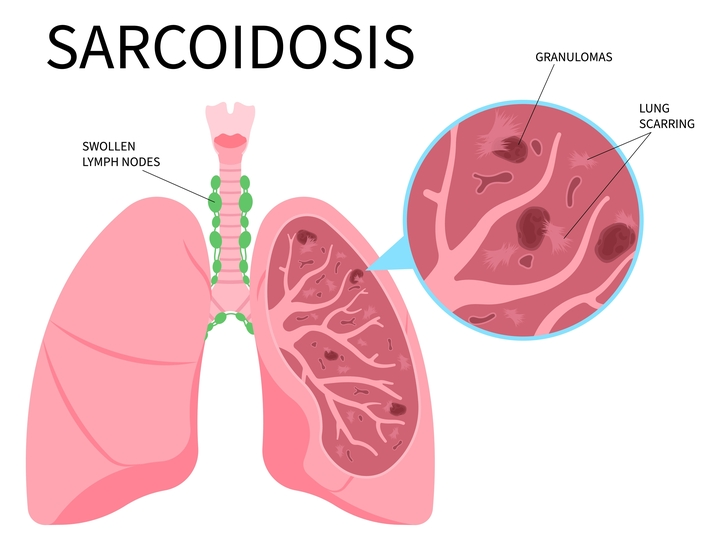

Explaining Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disorder that affects women more than men and can result in fibrosis in the lungs and other organs. Typically, sarcoidosis is thought of mainly as a lung disorder since inflammation occurs in the lungs in about 60 percent of patients regardless of any other organ involvement.

When sarcoidosis is present in other areas of the body without lung involvement, the diagnosis is harder to make and may be delayed. In Elaine’s case, she had no lung involvement, making the original diagnosis difficult, as was determining that any flare of the disease was occurring.

Neurosarcoidosis is a condition where granulomas form in the brain, resulting in altered mental status and personality changes that can mimic dementia and other neurologic disorders.

Elaine was originally admitted to our nursing home for short-term rehab. Her primary diagnosis was post-surgical aftercare for her left tibial fracture. Post-surgical care and maintaining her partial weight-bearing precautions should have been the most relevant medical condition to monitor.

At the acute care hospital, her main diagnosis was a fall resulting in a left tibial fracture. While her confusion was acknowledged, this was felt to be a minor problem that could be followed up by her primary care physician and should quickly clear.

When she arrived at the nursing home, the reason for her admission was already set: She needed rehab for her tibial fracture, which was complicated by her partial weight-bearing status, necessitating time for healing and education. Typical short-term rehab following a tibial fracture with nailing requires an average of two weeks before the patient returns to the community.

Because I interviewed her and examined her on the day of arrival, I was able to determine that her confusion would be a major barrier to her recovery. Upon superficial conversation, she seemed conversant and neurologically stable. But with deeper open-ended questions, her altered mental status began to be exposed. Though she seemed to know where she was, she mixed up details from 20 years ago with the present day and would occasionally add confabulations that were fanciful and incongruent.

Once we established a diagnosis connecting Elaine’s original fall and her current altered mental status, I was able to meet with the therapy and nursing teams to set expectations moving forward. We were able to develop a more complex but comprehensive plan to help Elaine and keep her safe from further injury.

Long Road to Recovery

Although therapy was started, Elaine’s ability to comprehend instructions and remember them for future application was, at first, nonexistent. What started out as a two-week rehab ended up being a two-month skilled nursing stay. Progress was slow, and more time was spent stabilizing her medical condition than on actual rehab advancements.

On top of the altered mental status caused by her disease process, she suffered steroid psychosis. Improvement remained slow, as was the steroid taper. Elaine followed up with the rheumatologist, and immune-modulating drugs were added to her regimen, allowing for continued tapering of the steroids.

Despite two months in the skilled wing of our nursing home, working extensively with me for medication management, along with aggressive daily physical, occupational, and speech therapy, Elaine was unable to progress far enough to permit a safe return to her home alone. She continued to require assistance for all aspects of care, including mobility, dressing, bathing, and carrying out tasks of daily living.

Eventually, Elaine transitioned to the nursing home’s intermediate care ward, otherwise known as long-term care, which provided her with the 24/7 nursing care assistance she needed. The rehab team continued to closely monitor her progress within her maintenance rehab exercise program, adjusting her care as needed to promote her independence.

For my part, I continued to manage and monitor her medications and blood work for any adverse outcome that might have been expected from immunomodulating medications and assessing her neurocognitive function.

After 11 months of medication adjustments, tentative nursing care, and excellent rehab support, Elaine was finally able to leave the nursing home and return to the community, successfully living alone.

It took Elaine just shy of one year to get back to the point where she could safely live on her own again, but with the proper diagnosis and care, she gradually made great strides and maintained her courage and resilience through this extended health challenge.

In retrospect, it became clear that the reason for her fall was due to a flare of her neurosarcoidosis that created an unsteady gait. Although her fracture was stabilized in the hospital, without understanding the cause of her fall, she was at risk of falling again and sustaining new injuries or messing up her recent surgical repair.

The root reason for the fall, however, was not understood until she arrived at the nursing home. It then took the combined efforts of the medical and rehab teams to stabilize her condition and allow her to fully recover and eventually return to her normal life.

Nursing Homes Have Evolved

Elaine’s case reminds us that nursing homes today are not the same institutions that they were 20 to 30 years ago. The convalescent center to which your grandparents were admitted in their later years to receive help with activities of daily living has now morphed into a free-standing medical/surgical ward. What used to be the convalescent center your grandparents knew is now called an assisted living facility. And the free-standing med/surg ward that is today’s nursing home is more like a hospital—but without in-house X-ray, pharmacy, or laboratory services.

Because these ancillary services are not available in the building, the cost of providing care to a patient in the nursing home is about 20 percent of the cost of providing care to the same patient in the hospital. For that reason, Medicare and insurance practices push for patients to be transferred to a nursing home earlier to reduce the cost of care. Hospitalists are under pressure as well to stabilize a patient as quickly as possible, treat the major diagnosis that resulted in hospitalization, and discharge the patient to the nursing home or community—whichever is safe and expedient. The expectation is that any other medical conditions surrounding the acute hospitalization can be addressed in an outpatient setting.

In Elaine’s case, that meant that she was in the hospital to treat the fracture resulting from her fall. The cause of the fall was not determined but assumed to be vertigo. There was no further evaluation of what could have caused her balance issues that resulted in the fall.

Elaine was fortunate to arrive at a nursing home with a full-time doctor so that she could be assessed immediately upon arrival. Most nursing homes do not have a full-time physician on staff. Despite recognizing that these institutions are free-standing med/surg wards, most nursing homes have not seen the need to adjust the level of their medical coverage in-house. They are required by law to have a medical director to oversee quality of care, but they are not required to have a full-time physician on staff. In my experience, that results in a huge difference in quality of care.

Medicare rules and regulations state that a doctor needs to see a patient and perform a history and physical on a new nursing home resident in the first 30 days. Although many doctors who attend to patients in nursing homes show up before 30 days have transpired, most are not there on the day the patient arrives. Instead, they look at the hospital notes and talk on the phone to the nursing staff to confirm initial orders sent from the hospital.

Based on reports from nursing about Elaine’s confusion, most doctors would have given orders for medications to suppress her confusion and help her to be more compliant with care. No workup would have been performed initially; instead, Elaine would most likely have received antipsychotics to moderate her symptoms of confusion. At the very least, she would have had a significantly delayed diagnosis or been diagnosed with dementia and left on medications to control her symptoms.

Furthermore, without the proper diagnosis and education of the staff by the doctor, therapy would have no doubt given up months earlier, determining that, due to her “dementia” or altered mental status, she was not capable of making progress with therapy and concluding that continuing therapy was futile. Understanding her medical condition and the medications she needed, however, was the catalyst that allowed therapy to modify goals and continue to work with her, knowing that her cognition would improve, even if at a slower-than-usual pace.

Many nursing homes have agreed that, due to the complexity of cases they are now taking on, they need a full-time nurse practitioner or physician assistant on staff. They feel that NPs or PAs can handle these cases, and they are less expensive than a full-time doctor.

In Elaine’s case, a nurse practitioner at the hospital had acknowledged her confusion and assumed that vertigo was the cause. The nurse practitioner was comforted in this decision by the notes from the internist as well as specialists on the case.

Hospitalists are pressured to address the admitting diagnosis and stabilize that medical condition as quickly as possible to minimize the length of the hospital stay. For the few days Elaine was at the hospital to stabilize her fracture, it was simple to assume the confusion was new and simply due to recent anesthesia. As a former hospitalist, understanding how colleagues are pressured to stabilize the admitting diagnosis and not extend the workup or increase hospital days made it easier for me to question the reason for her confusion and perform a more thorough evaluation to ensure the full story was understood and addressed. This is why doctors working alongside NPs and PAs in both the hospital and the nursing home setting provide the best response to quality-of-care outcomes.

Full-Time Doctor Benefits Nursing Home, Patients

Neurosarcoidosis is not the only difficult diagnosis that can face a clinician in the nursing home setting and accepting the diagnosis of other clinicians at face value can lead to poor patient outcomes. In Elaine’s case, this could have resulted in her never returning to a normal and productive life.

Although accepting the hospital’s diagnosis can be safe in most cases, being a clinician in any setting requires not just medication reconciliation between transitions of care, but also careful consideration of diagnoses already made in the context of one’s own skills at performing a history and physical, along with an inquiring medical mind.

This is why allowing 30 days for a physician to see a patient in the nursing home for the first time is not safe or even a good expenditure of Medicare dollars. Even if corrections can be made, spending 30 days on the wrong plan of care cannot be helpful for the patient or the cost of delivering health care.

At the end of the day, Elaine had a great outcome. She struggled through a year of confusion, depression, and frustration with slow progress. At times, she felt terrified that she would never leave the nursing home and that her life was over. However, with an understanding of her disease process, close monitoring, counseling from her psychologist, and the proper diagnosis, she has mostly recovered. Although she has not been able to return to work yet, Elaine is ecstatic to be back at home, recapturing her independence and resuming a normal life.

In past years, your primary care physician knew your whole history and followed you throughout your life, evaluating all your ups and downs. Now, you are treated by a team of professionals, most of whom have never seen you before, and you are ushered rapidly through different venues of care.

If you are unable to speak on your own behalf due to altered mental status, it may be hard not to get lost in the shuffle. But it should not be left to chance that you just happen to end up at the right facility in order to regain your life.